‘You urge me to make a new work from the old’, was Jerome’s complaint in the year 376 to the request from Pope Damascus for him to create the Vulgate version of the Gospels which were to be the creative foundation of some of the greatest manuscript art. Jerome agreed that there were too many inconsistencies in the existing Latin versions and that a new translation based on the older Greek texts was necessary. The insular monks seem to have supported the transmission of Jerome’s Vulgate when it made it to Ireland, with the occasional amendment.

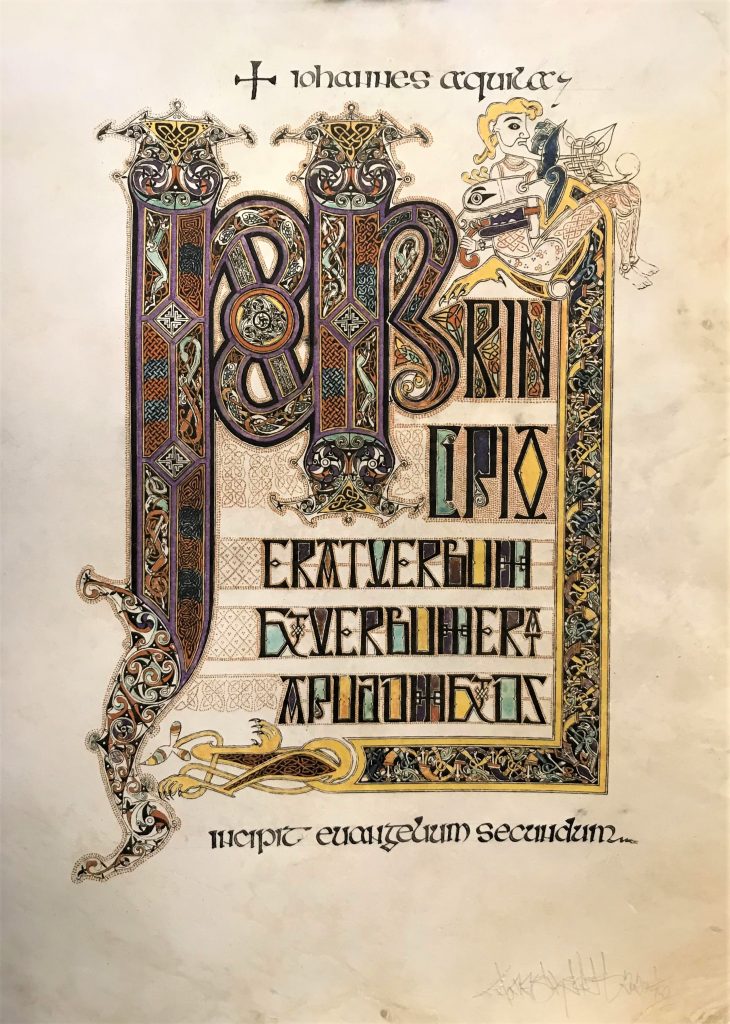

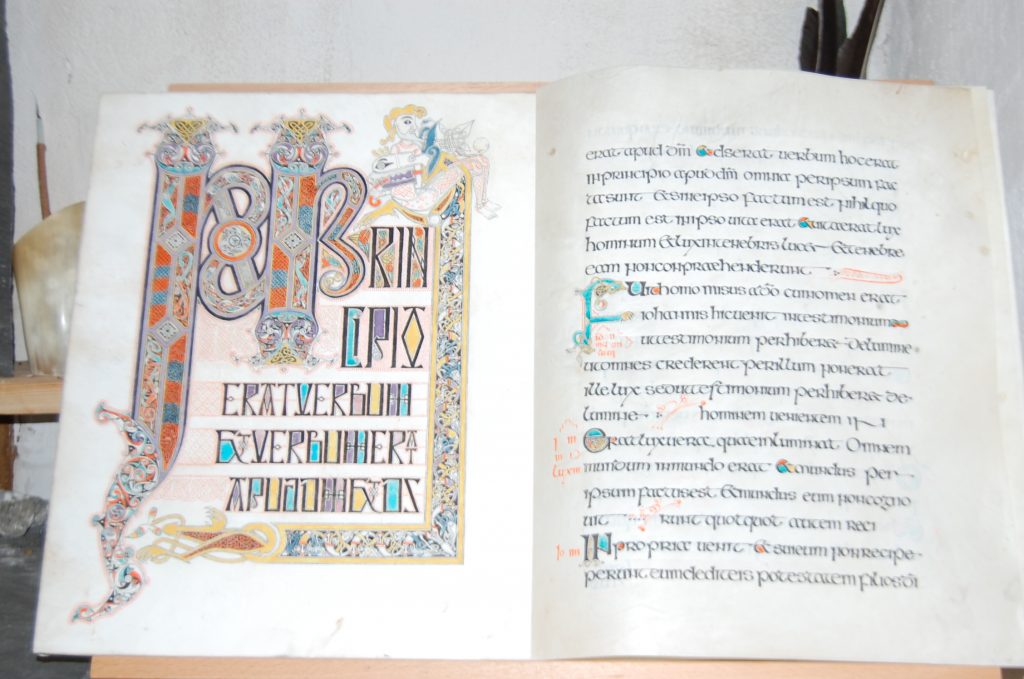

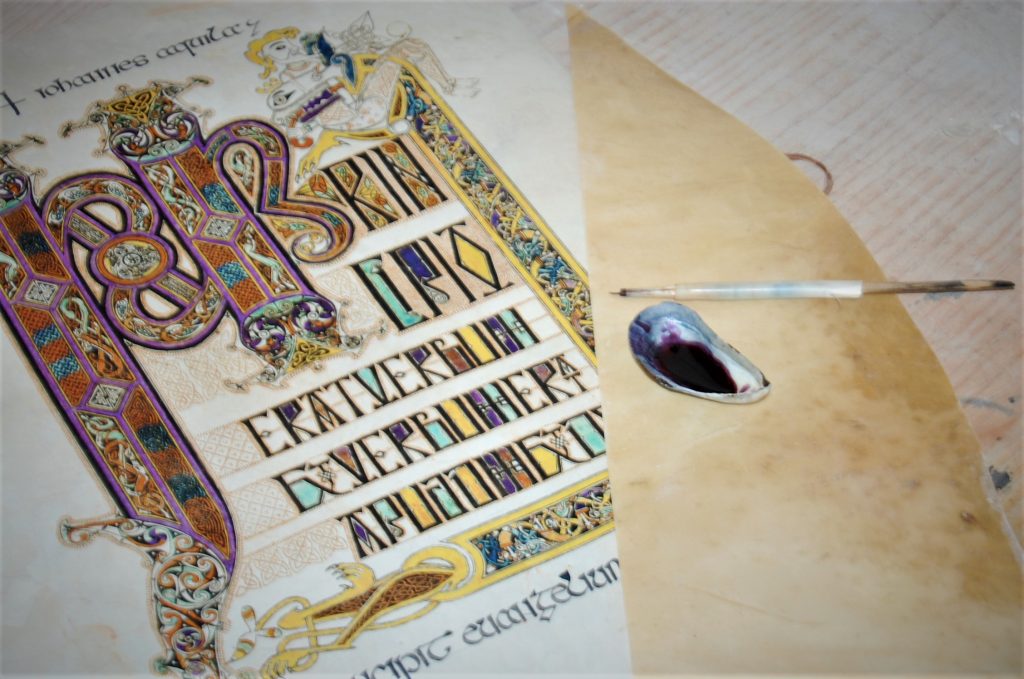

It was George Bain who discovered the Book of Kells’ scribes edit of the opening words of the Gospel of John, changing one of the VERBUM’s to VERUM so to ‘In the beginning was the true word’, possibly in an attempt to get closer to the meaning of the older Greek version.

The Rosemarkie Gospels are in this respect more orthodox, sticking with the Vulgate VERBUM as the scribe Aedfrith did in the LIndisfarne Gospels. No doubt his contemporaries at Rosemarkie could have done so as well to avoid any accusation of being influenced by ‘the poisonous weeds planted by the Scots’ as the eminent abbot Wilfrid liked to refer to the Columban style. These days no one’s going to accuse you of celebrating Easter on the wrong day if you write in Insular Majuscule rather than the more Roman Uncial but we do have our own problems to contend with and the new work that is made from the old must negotiate and reflect the concerns of our own time if insular art is going to be passed on for another 1500 years.

So why not just make paper giclee prints? Firstly on a practical level you just can’t fake the effect that real parchment gives to a work of art, it is translucent so the image appears to subtly float, insular art is designed to take advantage of this effect, if the parchment is removed then you might as well just copy, paste and print the image straight off the internet. The wonderful thing about manuscripts is that they can never be truly commodified or industrialised, the experience cannot be downloaded, real parchment needs to be seen, and for the lucky few, handled.

If there does need to be more art, it certainly does not need to be produced in industrial quantities and it would have to be of extreme merit to warrant adding more pollution to the world. The Insular culture has a long track record of producing small batches of low impact, highly durable artwork. The original scribes didn’t go on about it, but now it’s time to. Artforms and crafts that don’t become sustainable at quite a pace won’t be around for much longer and if business as usual continues in Celtic art as well as all other industries neither will the rest of us.

In medieval times deer hides were so valuable that it was worth risking death by breaking the forest laws to go poaching and get one. These days in the Scottish Highlands they are a waste product, there are too many deer with no natural predators and whilst there are game dealers doing a great job at promoting venison and ensuring the meat is used, there’s still a lot of work to do to find uses for the vast amount of skins being generated.

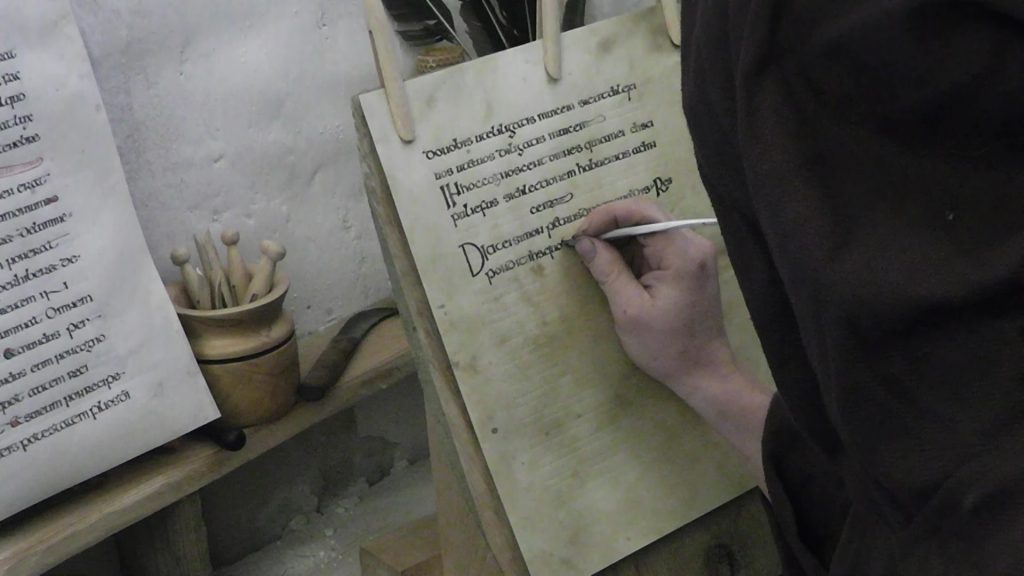

The deer skins for the parchment are all collected from the Highlands, at most 30 miles from where the parchment is made. They are soaked in lime much of which is produced from burning oyster shells, another waste product, then rinsed and stretched on a herse before being dried and scraped to produce a smooth writing surface. The ink with which the prints are glossed is made from the bark of a storm felled oak tree in Cromarty, mixed with the gum from the cherry trees growing beside it and ferrous sulphate produced by bacteria living on iron pyrite nodules.

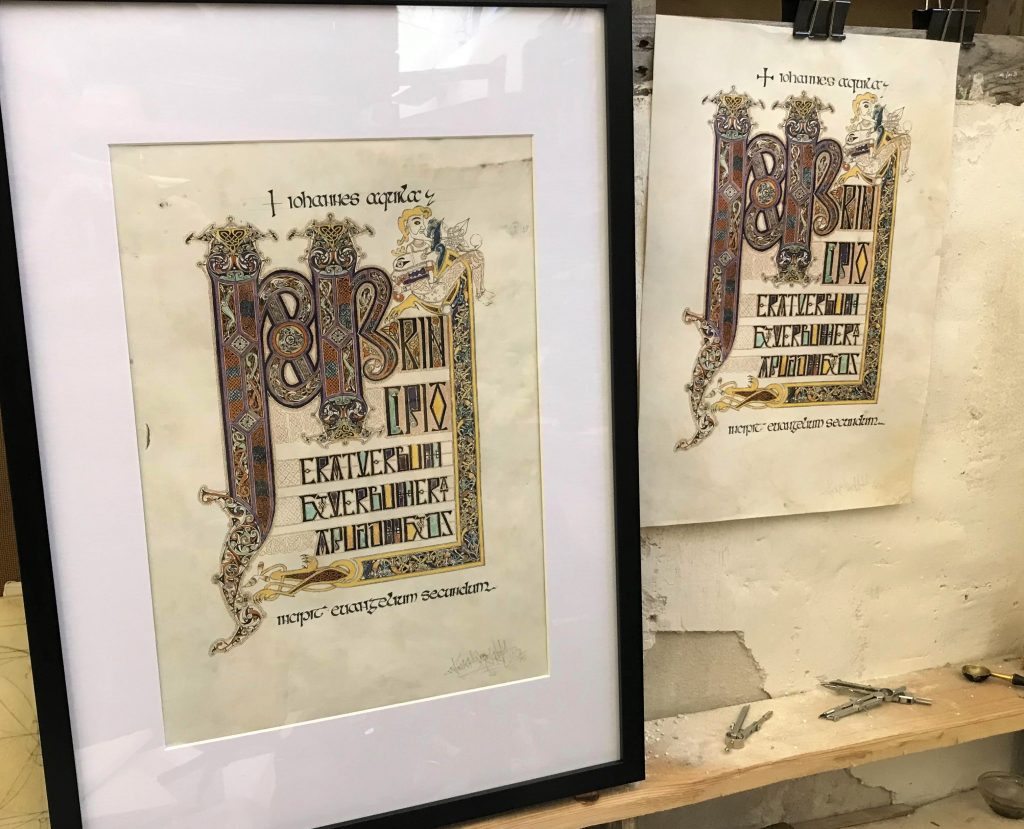

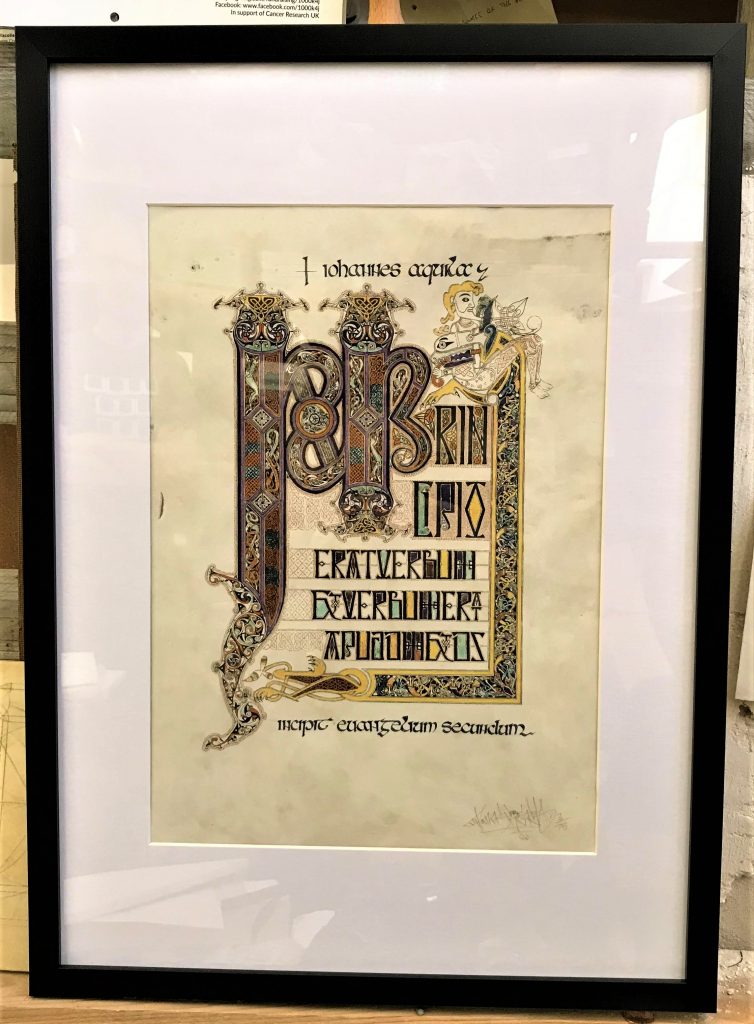

The innovation that brings this ancient craft into the 21st century is the combination of digital skills and a top of the range inkjet printer. The artwork on my Rosemarkie Gospel incipit was digitally lifted off the original parchment by Carsten Flieger in Cromarty. Then at Alder Arts in Beauly the complex process of tricking a digital printer into printing on real parchment begins, it takes some effort to make the printer accept the parchment and more digital wizardry from Drew Hardiman to get the colours right, especially difficult as each sheet of parchment is unique with its own hew and blemishes.

Despite this effort the prints don’t come out perfect, the orcein pigment can’t be completely matched without throwing the rest of the colours out of balance, it has to be retouched in real lichen fermented orcein on each print. The rest of the process is also reliant on traditional techniques. The gloss calligraphy IOHANNES AQUILA, INCIPIT EVANGELIUM SECUNDUM is added in oak bark ink with a swan feather quill. The prints are signed with a pewter stylus, a blend of tin and lead smelted specially for working on this specific parchment surface.

Here’s the result, they can be purchased at the Groam House Museum shop or online at www.scribalstyles.net. The edition is limited to 75, they are priced at £175 plus relevant postage.

See videos of the production processes at https://www.facebook.com/Scribalstyles-106490357652139

Post by Thomas Keyes.